This post is by Marta, our ex-resident, who’s recently moved out of The Salisbury Centre. She wanted to share her experience of living in community – and how it has changed her.

I wake up to the beeping sound of the door code input, two floors down from my bedroom. Someone is letting themselves into my home — a day like any other.

The door opens after a double “beep” signaling a correct code. Then, the other pair of door opens with a creak. My body knows it will slam precisely three seconds later.

It’s a meditation volunteer coming in just before 8 am to host a silent meditation. I look at the clock, 7:53. I spend a moment considering whether to join. I decide against it — I’m not up for rushing out of bed this quickly.

Will they be meditating on their own, or is someone joining them? That’s the question that’s bouncing around in my mind as I go to the bathroom. I don’t know.

What I do know is that, by now, I am pretty well tuned into the heartbeat of this building, this community, this hub for spiritual, psychological, and creative growth.

The Salisbury Centre is all of those things and, for 1164 days, it also happened to be my home.

I haven’t written anything personal for a while. Partially, it had to do with living at the Centre and having a chunk of my community read my stuff. This has changed my relationship to writing — specifically, who and how I write about.

Over the past three years here, I crossed paths with hundreds (if not thousands) of people here. I immersed myself in the world of relating, communicating, connection, and community. Naturally, these were the topics I felt inclined to write about. At the same time, I often wasn’t sure how people reading this may receive the stories that they are a part of.

But today, I’m putting those questions on the side. In 10 days, I’m moving out. And I need to write this, to honour the past 3+ years and all the people who were a part of my experience here. Whether you brought me safety, trust, triggers, or challenges — I value all of that and I’m grateful to you. You may or may not recognize yourself in this story and either way is fine.

Here’s to my first iteration of community living and all the learnings that came through. This is for everyone who already have done or want to do “community living.” Even though each experience is different, today I feel kinship with all of us who want to do life outside of the box and find our own way.

I hope you enjoy this and maybe find moments you can relate to.

The story starts with how, as The Salisbury Centre resident, I seem to have become an intrinsic part of the space. A friend with whom I used to live here, would say:

“People seem surprised to see me in a café, on the street, or in the shops. It’s almost as if they suspected I didn’t exist outside of The Salisbury Centre.”

I get what she meant. Living here, we become somewhat a part of the building, a fairly constant presence among many moving pieces. It seems that some people associate the residents with the community so much that it almost feels like we don’t exist outside of the Centre.

It’s funny, but also has a profound aspect. I don’t want to go into unnecessary self-indulgence. But, I do feel that the quality of my presence here has been one of my biggest responsibilities to The Salisbury Centre.

My home is a place which for most people acts as their precious

third place. How I welcome them into this place matters. Just by probability, I’m among the handful of people that they’re most likely to encounter and interact with here. Knowing that I’m involved in many of those interactions makes me aware that how I show up will impact how people feel here.

“Ray Oldenburg, an American sociologist, created this term [third place] to describe the places outside of the home (the first place) and the workplace (the second place) where people go to converse with others and connect with their community. In this casual and social environment, no one is obligated to be there and cost should not prevent people from attending. It is a place where we can interact with members of our community and even turn strangers into friends. At a third place, you might go to hangout with your friends, you might run into acquaintances by chance, or you might meet people you have never encountered before. It is a meeting ground to build relationships with others outside of home or work.” — The English Language Institute at The University of Chicago

Image. The Salisbury Centre garden.

The Salisbury Centre is a third place to many. It’s that to me, too. But what’s bizarre is that at the same it’s my home — my “first place” where I want to relax and feel my feelings without pretending.

That creates interesting situations because, at the end of the day, I need to do some social filtering here. I care about contributing to a good “third space experience,” so I don’t want to take my frustrations out on random visitors. So how do I honour my own flow while also enabling people I bump into to feel safe and welcome?

Even though there’s a private living area at the Centre, there are spaces where this overlaps with the public. Residents need to go to the communal parts for some of our personal affairs — such as the shower (right opposite the main entrance!), laundry, or taking out the bins. Visitors may catch me in a moment that would otherwise feel private, even intimate. So how do I respond if someone knocks on the front door as I’m passing from the shower room wrapped in a towel?

At the core, it’s about recognising the mismatch of context and expectations. While I’m in my “private” mode, a person approaching me right in this moment easily feels like intruder. But in their world, they are seeing a familiar face in a place they love. So of course they reach out enthusiastically to make connection. That’s the very thing they came here for.

As a community resident, translating between mine and other people’s contexts has been a skill for me to build. I have been pulled into the role of a host at random times, in different places, often unprepared. Of course, I wasn’t always ready or up for it.

What I have practiced was either getting ready for it in seconds, or graciously withdrawing when I needed to.

The blend of authenticity, respect, care, and boundaries was the cocktail I needed to perfect here. This recipe has been helpful in connection to the wider community — as well as fellow residents.

On the surface, co-living here resembles other flat shares. We pay rent. We have our own bedrooms. We share house chores and basic expenses. We have a living room which allows us to hang out when we want to.

However, the stakes for maintaining good house relationships are higher. That’s mainly because of the caretaking of the building that has traditionally been part of the residents role. In my three years of living here, this meant taking turns with my housemates to check if everything was in order each night. Putting the event rooms back to their default state. Making sure the doors and windows were shut. Unloading the dishwasher. Hanging up the laundry. Taking the bins out. That kind of thing.

I come down the stairs and start my usual routine.

First, turn to the left. Check Art Room and Wellspring Room. These are typically straightforward, as one of the past residents said — an easy win that makes you feel like you’ve accomplished something. It’s a good feeling to have before venturing into the kitchen, which is more of an unknown in terms of the amount of work awaiting.

I bargain with myself: Do I go upstairs and rush them to get out? Or do I cut them some slack?

Seeing the dishwasher needs emptying, I decide to start with that. I will give them a few more minutes before I knock on the door. As I unload the dishwasher, I notice my body surrendering to a well-known sequence of moves — mugs and glasses first, then plates, cutlery at the end.

In some ways, I have become one with this space, its objects and appliances.

I collaborate with them.

This is one of the evenings I’m able to go the extra mile and find patience. I smile to myself, knowing it may not last until tomorrow. As I remember that, I hear people leaving the Studio. Great — this means I won’t need to be that nagging person kicking them out tonight.

The small jobs and responsibilities have symbolized my personal commitment to The Salisbury Centre — as well as my co-residents. Because of our shared responsibilities, we needed to be a team.

Even if our relationships hit an edgy moment, we needed to find a way to communicate. That meant making sure that “the rounds” (as we came to call the caretaking duty) were taken care of each night. This included relying on the help of others when the place was left a complete mess (yes, I’m looking at some of you, evening private hirers!), as well as empathy needed to step in even though it wasn’t “my turn.”

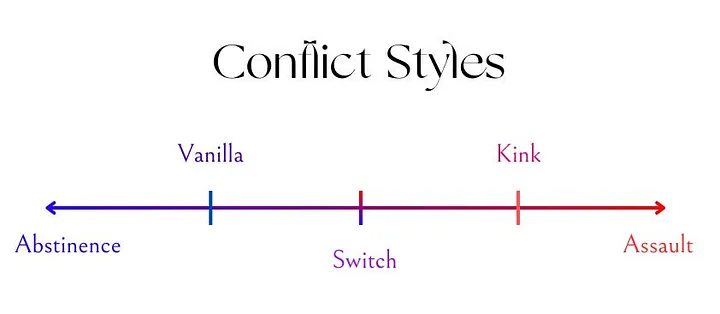

It’s quite a thing to be on a team with people you didn’t necessarily choose while also living with them. With one resident in particular, her and I had very different ways of communicating. It was a challenge for both of us to reach out from across the two different edges of the conflict style spectrum.

Here’s why Sara Ness likens conflict styles to sex terms, which she further defines in her Substack:

“I like the idea of comparing conflict to sex because just as many of us have sexual trauma, many of us also have trauma with conflict. We just don’t go to a therapist as often for the second one. (…)

I believe most people have a center of preference on this conflict style spectrum, but each relationship has its own fingerprint. With your boss you may err towards vanilla, while with your partner you feel comfortable in kink.”

The dynamic with the co-resident I’m talking about was me leaning towards vanilla, and her being more in the “kink” realm of the conflict spectrum. This meant that sometimes, we were able to talk things through but often — we weren’t. Yet, we still needed to collaborate.

It was a precious learning to figure out how to put my needs and preferences on hold for the greater good. Just to be clear — I didn’t like doing it very much. Being a sensitive and relatively privileged human being, I would have liked to resolve personal grudges first, before moving on to the practical.

Image. Dinner in The Salisbury Centre residents’ living room.

But sometimes, this proved impossible. I had to acknowledge that life is like that a lot of the time.

As a species that evolved to collaborate in order to survive, we used to know this. But as Sara Ness points out in another Substack article, our culture currently teaches us something else:

“There are few situations in modern life where we have to learn to give up our individual needs for the collective good, every single day. We have no learning or formula for prosocial development. We have lost the skill of positive negotiation, humble collaboration, and letting others win. We are no longer raised with these norms through the subtle (and overt) moral teachings of earlier ages, where our parents taught us respect, our society taught us courtesy, and our religion taught us generosity.”

It’s useful to know how to put our pride, hurt feelings, and grudges to the side to make something bigger happen. It’s not necessarily comfortable— but often, it’s exactly the way to create a world we want to live in.

I’m grateful for having had a playground to learn this at The Salisbury Centre. Hopefully, I can use this learning in other places, communities, and projects in the future.

I’m in a rush. I should have started my workday half an hour ago. I already know I will struggle to achieve everything I wanted today.

I come down the stairs, ready to get out. And then, I run into this person who’s striking up a conversation with me. For a few moments, I resist, wanting to get out as soon as possible. But suddenly, I find a moment of opening. Something they said inspired me. I manage to respond from a place of engagement and presence.

This is how the priorities for my day shift.

Suddenly, I see this human in front of me in all their glory and vulnerability — and I know I’m the same. I let go of my arbitrary timing because I recognise that what’s happening here is important. It’s precious and it’s real; two humans who’ve never met before are opening up. I don’t want to rush this. I let the interaction come to a natural end.

Then I leave the building — not much later than I thought, actually. But my state is changed. My step is lighter, mind is clearer, heart more grateful.

I remember: this is what I live for.

The Salisbury Centre helped me learn how to open up on purpose. That’s different than forcing a conversation, or being coerced into sharing something I don’t want to.

I’ve been learning to feel that subtle difference in my body.

I can’t always do it, of course. There are moments when my defenses are up, or it just doesn’t feel right. And of course, my agenda can actually be more important than in-the-moment connection. That’s just part of life.

But living here, I discovered that the state of open heart is within my control. It can be encouraged by effort, intention, and practice. When the moment is right, I can choose to prioritise it — and as a result, have moments of meaningful connection sprinkled throughout my days.

Living in a community of spiritual seekers has meant that the opportunities for those moments were literally at my doorstep.

On that note — can you imagine that the door of your house is pretty much open from morning till evening? That, even when you’re not around, anyone can come inside from the street, and you don’t have control over it?

This is kind of how I’ve lived for the past three years.

Of course, in practice the door isn’t literally open. People have to have a code to get in, which is only known to facilitators and event participants. After the event is over, the code expires. People can no longer enter.

Nevertheless, that’s already a large pool of people coming into my home! The residents area isn’t separated from the communal area even by a door. All you have to do is come up the stairs — and you could be in our living room, bathroom, or bedroom.

Strangely enough, I never felt the need to lock up my bedroom — except for a few weird nights when I heard noises I couldn’t explain and my imagination ran wild. But in general, the notion of other people being around didn’t feel like a threat. Most people can be trusted not to invade the residents’ space. Only occasionally, there would be a lost yogi wandering up the stairs, hoping to find a yoga class in my bedroom. Or, staff members knocking on our living room door with a “quick question” while we’re in the middle of a meal.

All of that was funny on good days and annoying on bad days. But not once can I remember perceiving it as a threat. That’s a remarkable step on my journey of feeling increasingly safe in the world.

Living at The Salisbury Centre has helped me build trust in people. I learned that stranger doesn’t equal danger. Some have said that it’s the strong intention that has been put in by the founders of the Centre over fifty years ago that has kept the space safe. It’s like an invisible cloak of energetic protection. And I don’t know exactly what that is — but I feel it.

People told me that, over the years, there have been things that could have gone terribly wrong here. Experimenting with illegal drugs. Different types of misconduct. Financial trouble. The Centre closing for a period of time in 2012 — but then, a group of caring people gathered, cleaned, and re-imagined the Centre, so its mission could continue.

This place has a strong protection rooted in history, tradition, and possibly more subtle energetic things being at play. The Salisbury Centre has continued for over 50 years now. To me, that carries a strong possibility that it will persist, if we people continue to trust.

“Oh yes, I remember this orange pot. It’s even on the photos from our dinners 30 years ago. I can’t believe you’re still using it!”

“This was the time we started using the well again… I made a personal commitment to the well, coming down to draw water from it for three months every day, until fresh drinking water emerged.”

“As residents, we were responsible for running the Centre. We all had shifts for when we were opening the door, hosting events, cooking, running classes… This was at times exhausting but also deeply satisfying!”

“Right here in the attic, we meditated together every morning without fail. This was our foundational practice, the focal point around which we built community.”

— overheard during the 50th anniversary celebration week

The Salisbury Centre taught me a lot about ancestry, stewardship, and a lineage of people guarding its tradition. Of course, the place has changed over its 50+ years of existence. It is different now than back in the early 1970s when it started as a project ran by a group of students.

And yet… During the 50th anniversary celebration in 2023, I heard people talking about the “essence of the place” that, at its core, remained unchanged. Someone who’s lived here 40 years ago came all the way from Canada, looked at her old bedroom (which happens to be my bedroom now), and said: Yep, this is very much the place I remember.

Hearing that, I felt puzzled, intrigued, and in awe. What is so strongly “here” that people can recognise it decades later? What is the purpose The Salisbury Centre has served in its wider ecosystem of Edinburgh and Scotland? What are its unchanging qualities that warrant its continuity?

Don Enrigh twrites reflects on such questions in the context of preserving heritage of historic places:

“Essence of place is the sum of the qualities, tangible and intangible, that come together to make that place unique on earth. (…) Defining essence of place can be a fun exercise, and sometimes a fairly abstract one. I would say that, after about ten years of doing this work, one of the most effective questions to bring into a discussion is to simply ask community members to fill in this blank: “Without _____, this place is no longer this place. It has lost something essential.”

still don’t exactly know how I’d fill the blank for The Salisbury Centre. Nevertheless, I can feel its strong essence, even if I can’t put it into words. This essence has given me an incentive to step up and become a more mature version of myself here. That’s because I’ve been trusted to continue to nurture this essence as a resident.

The Salisbury Centre made it possible for me to feel like I’m a part of something bigger that spans generations. What I do here matters. It’s like playing a part in a theatre play. On the one hand, it goes on wit or without me. But if my character was taken out of the plot, the story would be different. Even if just a little bit — but still.

Being a part of something that was created to last gave me an incentive to act more intentionally and live more consciously. What I do here isn’t just about me. It contributes to the future of the place and its community.

Regenerative philosophy is what I’m trying to get into here.

It’s the movement from the individual to the collective thinking. It’s a shift from short-term to the long-term orientation. It’s bringing focus away from single specimen and onto the whole ecosystem.

Let this quote from Regenerosity websitebringing it together:

“Regenerative design practitioners work to create and encourage healthy systems which create perpetual cycles of co-benefits, constantly strengthening the health of the overall system as well as each individual element. The co-benefits, inter-related and cascading, have an exponential potential to produce real change in the livelihoods and quality of life of those living in the region (…).”

The’Seventh Generation Principle means we create“socially and economically fulfilling lives for its inhabitants, whose daily activity patterns regenerate natural ecosystems and increase living capital year over year, such that the economic and social value of natural ecosystems is always increasing, and the value-ing of those systems is transmitted intact across generations.”

I only started getting what all of this means through living at The Salisbury Centre and interacting with my community here.

Of course, regenerative thinking is nothing new. It’s just in the Western, capitalism-driven societies that we need to remember this. Indigenous communities have been living with this mindset for as long as they exist. That’s because, in the grand scheme of things, that’s the only natural, sustainable way of thinking that will allow humanity to continue.

It’s only when the industrial era came upon us that we started trying to “outsmart” the natural order. That’s when we started shifting away from the collective needs of the ecosystem to the needs of individual specimen. For a few hundreds years, we’ve been trying to cheat ourselves that we can have it all without consequences.

As we’re all going through a collective, global wake-up call, I’m grateful to have been able to digest it at The Salisbury Centre. For the past three years, it’s been my informal “community college” that helped me re-member. I now seem to be a more conscious member of this planet, of my community, and of my own life.

The Salisbury Centre has changed me in the ways in which I needed to change. What this really means is the people whom I’ve met here. Thank you for all the lessons you’ve taught me so I can be in service, while also growing and taking care of myself.

I shall now take these lessons with me and implement them where I can — with the seventh generation in mind.